How do police and federal agents identify and target those who participate in demonstrations? What countermeasures can we take to hinder this kind of repression? In this anonymously submitted text, one affinity group explores how they address these questions.

Once upon a time, only those who intended to engage in high-risk confrontational protest activity had to concern themselves with surveillance and security. Today, surveillance and policing are becoming much more invasive and arbitrary. Even if you never violate any law, the state may nonetheless seek to make an example of you. Everyone who might participate in a demonstration at some point should familiarize themselves with the security protocols that radicals have developed over the years.

If you are new to demonstrating, do not be intimidated by all of these considerations. The more people take the streets, the safer it will be for everyone—and nothing could possibly be more dangerous than remaining isolated and passive, letting the police state come for all of us one by one. This guide simply outlines how to maximize your safety while engaging in protest activity.

For more general background in the subject, start by reading about how to form an affinity group in which to participate in demonstrations, how to plan direct action, and how to dress in matching clothing in a demonstration, in what is often referred to as a black bloc. The appendix includes a host of related material.

No Face, No Case?

While it is certainly a good idea to don a mask before engaging in protest activity, what clothing you wear is only one of many questions worth considering. You can reduce the risk of being arrested and prosecuted by applying an array of countermeasures—also known as operational security measures, or “opsec.”

If, despite your best efforts, you nonetheless find yourself in handcuffs, having thoughtfully applied these countermeasures will minimize the usefulness of any evidence against you. No trace, no case.

Preparing for the Demonstration

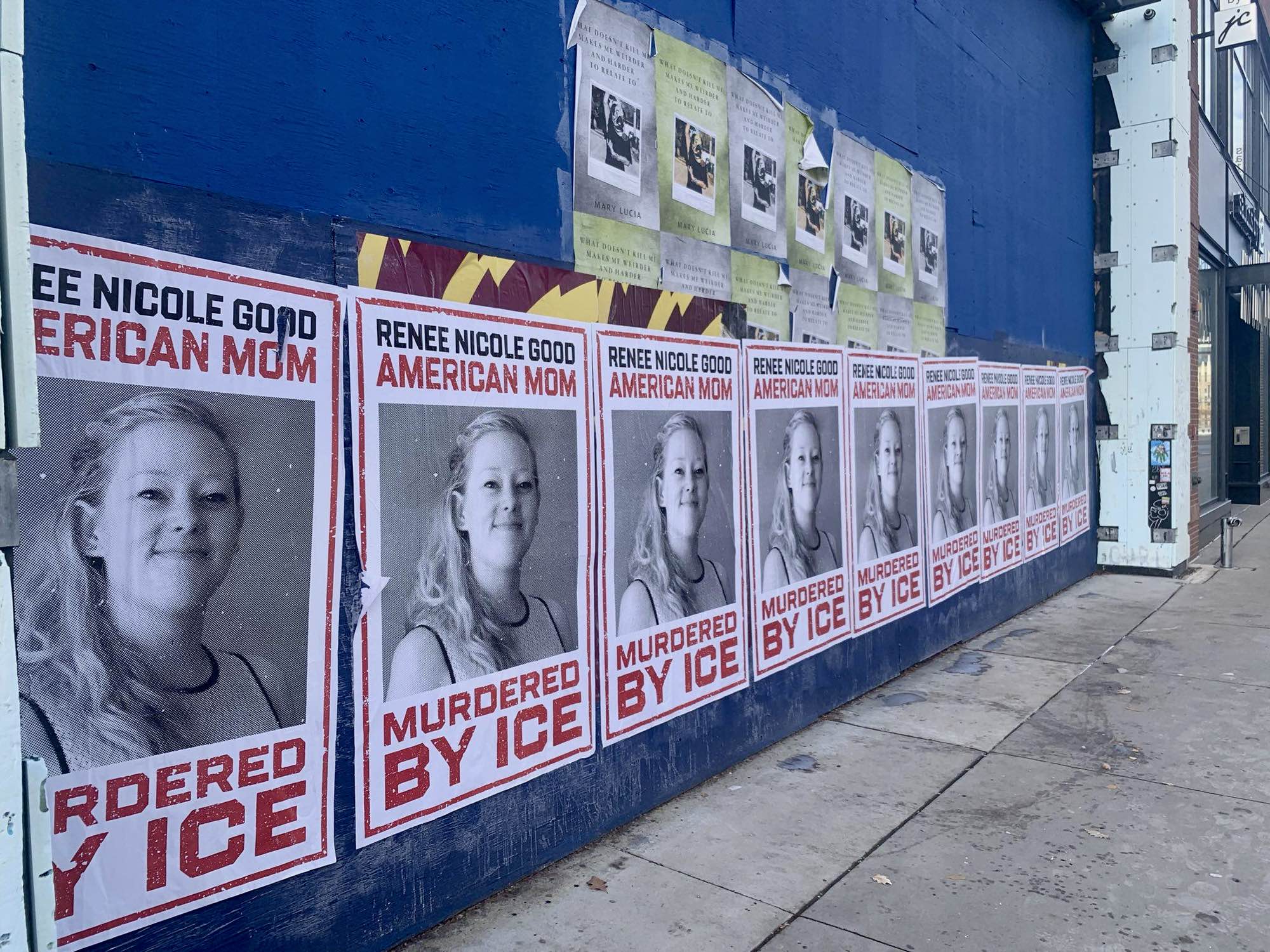

A demonstrator protecting their community from tear gas. Note how their jacket is hiking up, potentially revealing more than they intend. Make sure to pick clothing that will keep you fully covered in any position.

Honing Plans

When our affinity group meets to prepare for an action, we try to give ourselves enough lead time to go over everything. To begin with, what are our goals? Where is the demonstration taking place and what details do we know about the location? Do we have everything we need? Who’s bringing what, and how do we plan to get it there? Will others we know be coming as well? At what point will we want to leave, and how? Does anyone have particular fears or concerns?

Demonstrations can be inspiring opportunities to act effectively alongside other people. They can also be upsetting and traumatizing. It’s important to discuss any limits to your personal capacities that could be relevant to the rest of your affinity group. For example, does someone have an injury that could limit how much running they can do? Does someone’s choice not to wear glasses during a demonstration inhibit their long-range vision? How familiar are you with the streets in this area of the city? Are certain scenarios likely to trigger feelings of panic due to past experiences?

There is nothing to be gained from pretending we have no fears, traumas, or physical limitations. We want to support each other so that we can be as effective as possible together.

In discussions ahead of demonstrations, there is a tendency to make generalizations. “It’s always like this.” “It’s clear that the cops will act this way,” “This will definitely work.” It’s best to avoid definitive statements and remain open to what might happen. We try to focus on clarifying our personal goals and making sure that we will have everything we need to act when opportunities present themselves, while trying to imagine what the most likely opportunities will be. It’s a terrible feeling to see a window of opportunity open when you did not prepare adequately because someone said “that’s not going to happen.”

Try not to overplan. We aim for flexible preparation: we think about what we want to do and prepare to do it while staying open to the unexpected. We’ve found that if we discuss something for hours, it often proves not to be particularly helpful because events turn out differently than we anticipated. We’re not talking about small-group actions in the middle of the night that can be planned out in precise detail, but demonstrations involving a large number of people in which many factors develop dynamically. That said, knowing the lay of the land is important; it can help you to identify interesting routes and to outwit the police. Some demonstrations involve a pre-planned route; in those cases, it can be helpful to walk it beforehand to see where there might be good areas for changing clothes, bringing in material, and exiting. Make note of camera coverage, dead ends, bottlenecks, and opportunities.

But don’t underplan, either. Don’t take it for granted that someone else is going to kick things off. If you want something to happen, you may have to be that someone. Likewise, it’s better for a bag of materials to go unused than to lack what you need at a key moment.

If we want to bring tools or resources that could attract the wrong kind of attention and there is a risk of bag searches around the meeting point of the demonstration, we will wait to join the demonstration until it starts moving and the police shift their focus from monitoring the perimeter to crowd control. If we don’t know in advance which route the demonstration will take, those who are transporting materials use bicycles to get in and out; this also limits the amount of time they are visible to police flanking or tailing the demonstration. Hiding materials along the route can work, but too often, this has failed us after the demonstration took an unexpected turn; these days, we prioritize other solutions.

It’s helpful to think through how police tactics have evolved in your context. Is the local riot squad in good shape? Do they often use the tactic of “kettling” a crowd, blocking all exits to make mass arrests? Do they often target the meeting points of demonstrations in a particular way? What kind of tear gas do they use, and what situations have they used it in? When do they use rubber bullets? What other patterns can you recognize in their behavior?

Your local police department likely studies demonstrators’ tactics and develops crowd control tactics in response. These will also change depending on available personnel, police resources, and other issues, such as whether political or legal developments have made certain crowd control tactics impracticable. Demonstrations are inherently unpredictable, and it is difficult to anticipate what the police are planning on any given day, let alone what they will do if something surprises them. For this reason, we try to take a broad, historical perspective in our analysis, aiming to think through how the tactics and strategy of repression vary according to context rather than simply asking “What happened last time?” and expecting it to happen again.

For a more structured approach to planning, try “threat modeling”—considering the capabilities and motivations of your adversaries, reflecting on how you might be vulnerable to them, and deciding on countermeasures that will reduce those risks while enabling you to achieve your goals. For inspiration, you could take a look at the No Trace Project’s Threat Library and their tutorial, which explores threat modeling in the context of a black bloc.

To emphasize this—if you are planning for an action in a single small group, you should probably focus on achieving one or two concrete goals and remain flexible beyond that. If you put together a complex plan based on a series of contingencies that are beyond your control, things may not work out as you anticipated. If your plan does not allow for flexibility, it may be wise to carry out it out and then focus on leaving safely. By doing what you have prepared to do and doing it well, you may be able to create a context in which others can also accomplish their goals.

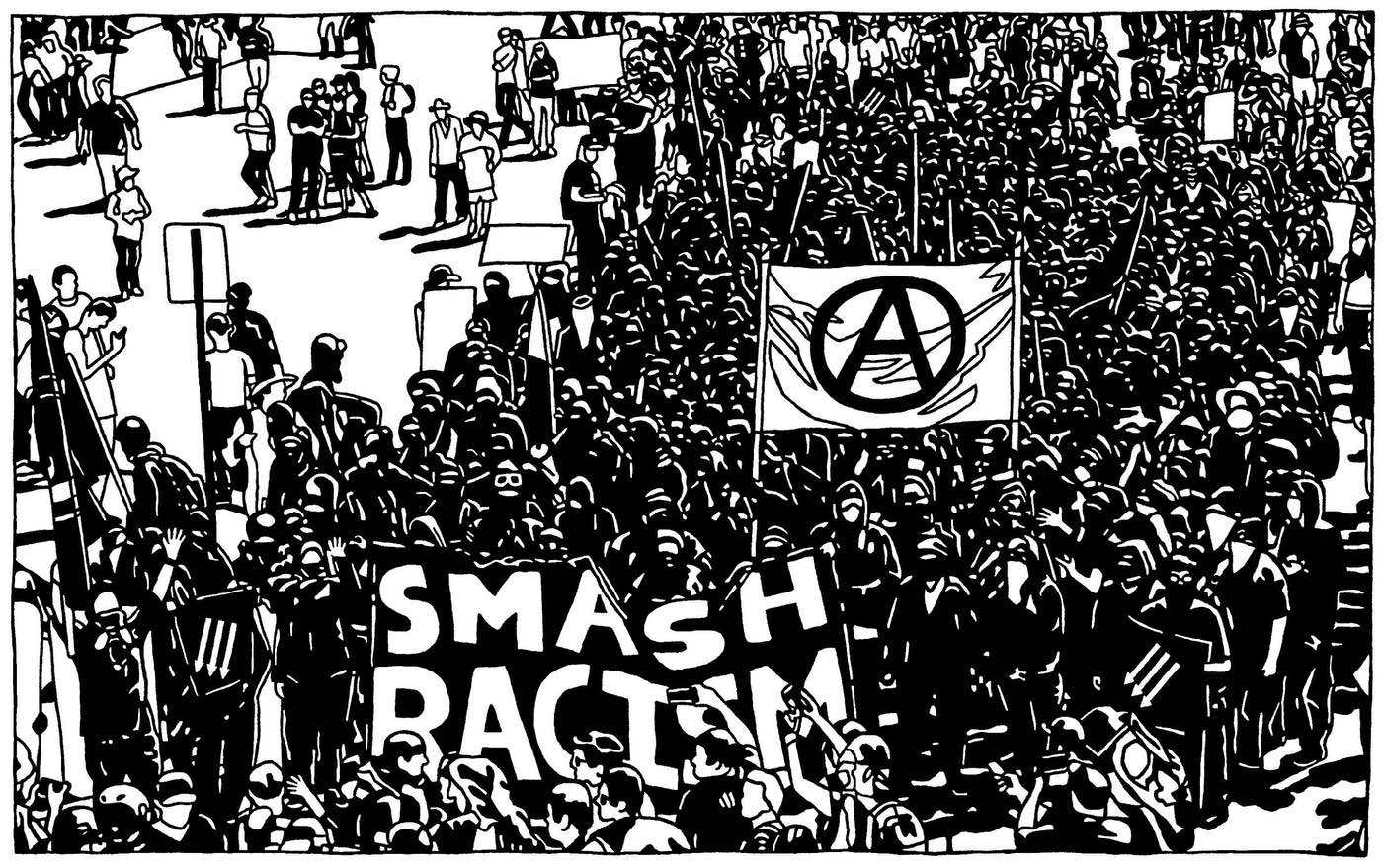

A black bloc demonstration in Bandung, May Day 2019. Photograph by Frans Ari Prasetyo.

Getting Everything Together

Obtaining everything you need to carry out a plan can cost money: gloves, new clothes, materials, travel, and other expenses. We try to share the costs among ourselves in such a way that no one experiences financial stress.

We make all purchases in cash, and we make any sensitive purchases in advance, spreading them out between different stores and wearing clothing that preserves our privacy, such as a hat and an N95 mask. For each significant item, we think about how investigators might be able to reconstruct where it was purchased and we remove any relevant serial numbers or RFID tags.

We treat any clothing that will be visible while participating in a black bloc as disposable. Some people wear their personal rain jackets and simply tape over the logos, but we consider this insufficient. If we participate in high-risk activity while wearing particular outfits, that will be the last time we wear them. We’re careful to minimize any features of the clothing that could be used to distinguish us from other people in the bloc. Sometimes it is enough to cover a logo with black marker or remove the stitching, but it is better to find items without logos in the first place. We prefer baggy clothing because it helps to conceal the shape of one’s body.

Here are some guidelines for shopping for a disposable layer, listed from head to toe:

- A black mask that doesn’t show eyebrows. One option is to fashion a t-shirt made of some breathable fabric (such as cotton) into a mask, as this can be tied to conceal the eyebrows and upper nose completely. Boxer briefs can also serve this purpose. Alternatively, it is possible to reduce the size of the eye holes in a breathable balaclava by adding a few stitches on each side.

- A nondescript pair of black sunglasses. Without eyewear, police photographers can take high-resolution photographs of your eyes and identify your skin color. To prevent these from fogging up, we apply an anti-fog spray [we recommend this one] to the lenses beforehand. You can swap these out for tinted swimming goggles in anticipation of pepper spray, or impact-resistant goggles if rubber bullets are a risk. If need be, you may be able to obtain prescription sunglasses or swimming goggles, since it is better not to wear contact lens if you might be exposed to chemical weapons. For night actions, you may need sunglasses with a lighter tint; always test your gear ahead of time in the same conditions in which you will use it.

- A nondescript black hoodie or jacket. If the police in your area sometimes use paint munitions to distinguish demonstrators, it can help to wear a second layer of black clothing that can be removed if it is marked . Waterproof clothing (such as a rain jacket) is best for this purpose, because it will hinder the marker dye from soaking through to your additional layers.

- A pair of black gloves. We like to use work gloves that have smooth rubber on the palms because they won’t tear easily, the palms are non-permeable, and they allow for good dexterity and grip. However, smooth rubber gloves can retain fingerprints on the outside and even pass them on to objects you handle; clean them before an action and take care not to leave prints on the outside while donning them. The alternative is to use cloth work gloves, though these can inhibit dexterity. If you may need to handle tear gas canisters, which remain extremely hot for some time after police deploy them, make sure to use heat-resistant gloves.

- A pair of nondescript black jeans. Optionally, to better disguise our body shapes, we sometimes wear black tear-away jogging pants over the jeans (easier for quick removal), or sweat pants (easier to find, and a small vertical cut can be made to the ankle fabric to facilitate pulling them off without removing shoes), or rain pants (better for withstanding paint munitions).

- A pair of large black socks pulled over shoes, taking inspiration from the anarchists in Chile. In several cases, the decision not to take this extra precaution has resulted in descriptions of footwear becoming the primary evidence in court cases. These socks must be a large enough size to fit easily over your shoes. To facilitate quick removal, use scissors or a knife to cut two one-inch slits along the ankle of each sock, one along the instep and the other along the other side; this will cause of the front of the sock to fold over, forming a “tongue,” which you can grab in order to tear off the sock rapidly.

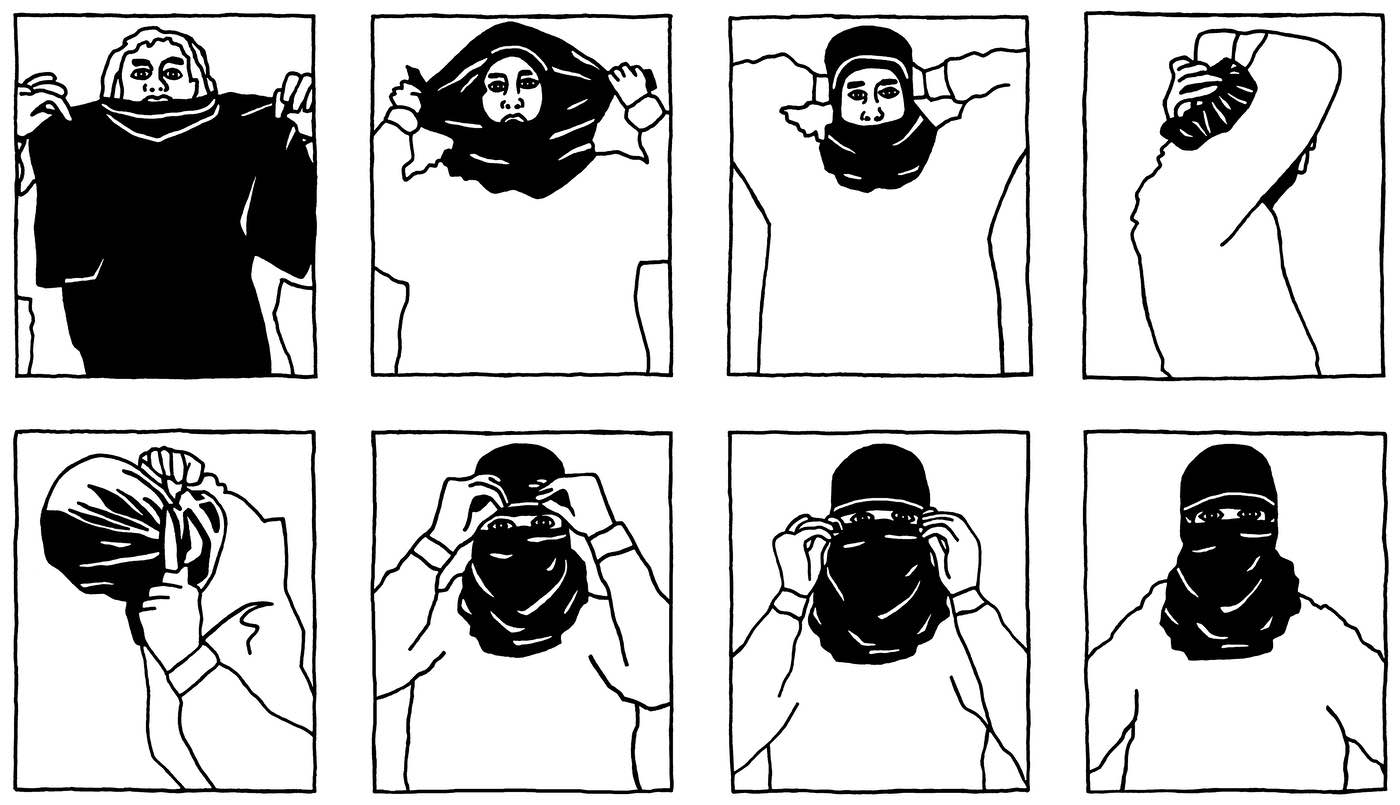

How to make a t-shirt into a mask.

Depending on how frequently demonstrations are happening, having to obtain clothes for each one separately can take a lot of energy, so we usually buy several of each clothing item and store the extras at the house of a trusted friend. Shoplifting materials offers one way to avoid memorable interactions with the person at the cash register, but if one is suspected of shoplifting, the store may keep the CCTV footage for longer than they would otherwise—and being caught in the act could enable the authorities to connect the dots.

When packing for the demonstration, we apply a “need-to-bring” standard, similar to the “need-to-know” standard we apply when sharing information about our plans beyond our affinity group. If anyone is arrested, whatever they are carrying could be harmful to them or others—a flyer for the demonstration could be used to establish that that the arrestee attended intentionally, the contents of a wallet could provide investigators with a wealth of new information, a day planner could reveal information about relationships. For this reason, beyond clothing and plan-specific materials, we keep it minimal.

Our standard is to carry a single piece of identification in case of arrest or injury, as well as some water and a few energy bars or similar snacks. If you take a daily prescription medication, you can bring a few doses in a prescription bottle in case of arrest. It is also important to have enough cash for a taxi or public transportation or to blend in at a café or restaurant afterwards. If relevant to the local jail context, you may need to bring coins for making a call in the case of arrest. Beyond that, leave everything else at home. Check your pockets and bags for stray items like flyers, receipts, zines, and notes. Even if you don’t get arrested, anything you bring is one more item that could get lost in the chaos to be picked up later and potentially linked back to you or others.

How to make a t-shirt into a mask. You can also use boxer briefs or other ordinary tight-fitting clothing items. In contrast to the model in this video, you should make sure to cover your eyebrows.

Keeping Everything Clean

After a demonstration, it’s common for a forensic team to search for items of clothing and tools left near the demonstration route or dispersal point—so it is important to be careful while handling, storing, and transporting materials.

We never touch any tools we plan to bring without wearing gloves, to make sure there are no fingerprints on them. It is easier to avoid leaving fingerprints on something in the first place than to rely on removing them with an acetone-soaked cloth, which can be less effective on some types of surfaces. For example, on a metal surface, fingerprints can leave an imprint which must be removed with an abrasive material like sandpaper.

In some cases, it may be important to try to keep materials free of our DNA. Skin cells, hair, saliva, blood, and sweat are all sources of DNA—and unlike fingerprints, DNA cannot be reliably removed from an object once it has been contaminated. A good starting point is to put on a fresh pair of non-permeable gloves (i.e., rubber dishwashing gloves rather than cotton or the like) before handling objects, without ever touching the outside of the gloves. The likelihood of DNA forensics being used seems to be directly proportional to how expensive the testing is in a given jurisdiction. Some countries already have forensic labs that enable the collection of DNA evidence even for the investigation of minor crimes, but in the United States, DNA testing is not yet common for evidence collection at demonstrations.

If DNA is found on a moveable object, the person it is associated with could have interacted with that object weeks earlier, so it is less convincing that someone was present at the scene compared to if their DNA is found on a stationary object such as a smashed window. It is impossible to avoid leaving DNA traces on clothing that has been worn, so we make sure not to leave clothes behind whenever DNA forensics is a consideration.

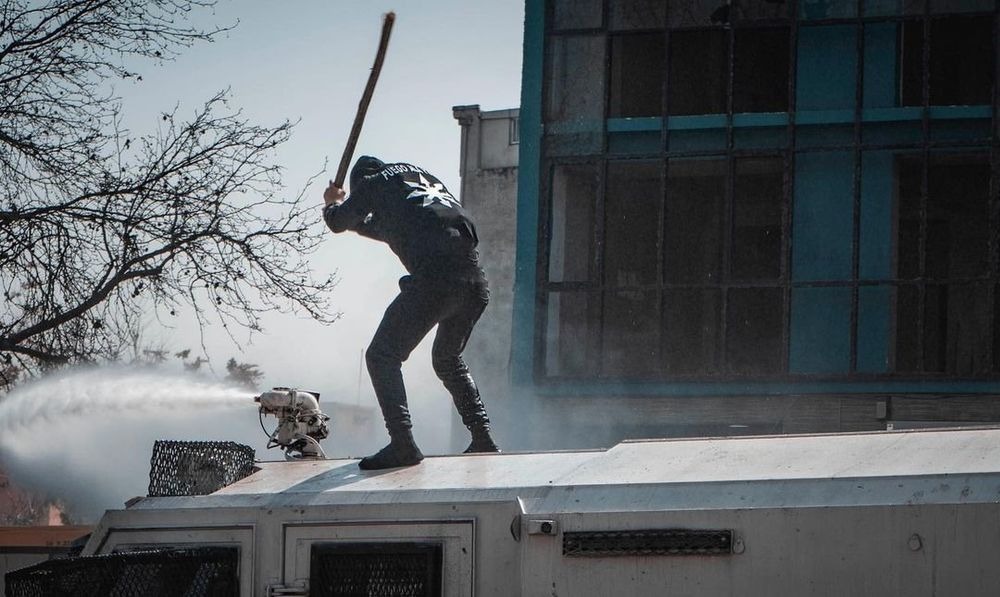

Note how this demonstrator in Chile has pulled socks over their shoes to conceal their footwear while endeavoring to protect their community from this water cannon. Mysteriously, however, they are not wearing gloves, and wearing a sweatshirt with a recognizable design on it.

Preparing for Repression and Raids

An essential element of preparation is planning for worst-case scenarios. Repression always hits hardest when you aren’t prepared for it. Finding yourself in police custody with no idea who will be your lawyer, take care of your dog, inform your boss that you will not make it to work, or pay your bail is rough. We prepare collectively for every demonstration as if we might be locked up for at least one night—for example, by having a lawyer on retainer and memorizing their number. This may sound emotionally draining, but we find that it actually empowers us to act more freely. Other ways of preparing could include giving someone a spare house key, arranging for child care or pet care, arranging for someone to pay bail or rent, sharing the logins for an email account or collective social media account, and the like.

Another important question to consider is—if police search your home for evidence, will they find any items that could help them build a case? Of course, everyone will have to answer this question contextually, but the important thing to remember is that one never knows when a house raid will occur or what the police might be looking for. Therefore, we should make sure that our homes are always as free as possible of materials that would be interesting to a prosecutor.

As a general rule, don’t store anything particularly sensitive at home. It’s not always the single incriminating item that is a problem, such as an article of clothing caught on surveillance footage—we also avoid what we call the sketchy collection. Some examples of things we don’t keep at home are fireworks, slingshots, too many items of the same type of clothing (gloves, masks, black hoodies), and the like.

Sensitive items must be stored somewhere, of course. One option is in the homes of trusted friends who are unlikely to experience a search themselves—though once again, in order to avoid creating a collection of items that look suspicious together, it can help to store different items in different locations, or distribute them between the homes of different friends. Another option is to hide items outdoors in a place no one will stumble upon them, where it is possible to access them without being observed (buried in a forest far from any paths, hidden in the ceiling of an abandoned building).

As for the items that we keep at home, we don’t store them on a “demonstration” shelf, we keep them where they belong—for example, a sealed package of gloves with the cleaning supplies. Our lawyer should be able to provide convincing, legitimate reasons for anything in our homes.

Demonstrators in Chile in 2019.

The Cop in Your Pocket

Police investigators often analyze the phone and computer use of suspects in order to try to build a case against them. The culture of smartphone dependence that has become normalized throughout society over the last decade makes their job much easier. On the other hand, whereas the state could once remotely monitor unencrypted voice calls and text messages, this is no longer the case thanks to the widespread adoption of encrypted messaging apps like Signal. The chief threats have assumed other forms.

When it comes to phone surveillance today, there are three main areas of concern: covertly activating the microphone, location tracking, and data retrieval.

Of these, covertly activating the microphone often receives the most attention, but it is actually the least likely, as it requires the most resources. The phone must first be infected with some type of malware in order to covertly activate its mic to turn it into a “bug.” Generally, this means that the device must be specifically targeted for infection.

As for location tracking, a phone’s connection to cell towers inherently reveals its location to the mobile service provider, and this location data can be accessed retroactively. Just by knowing a phone number, police can quickly map everywhere that phone has ever been and easily display patterns and connections over a given period of time—for example, the preceding year, or the week before the demonstration.

If one of us is arrested, even the dumbest cop or prosecutor may think to ask who we were with and where we were in the time leading up to the arrest. The automatic location tracking of cell phones makes this information easily accessible. Anyone who could be targeted for investigation should know that carrying their phone with them as they go about daily life can give investigators a more or less comprehensive understanding of who they organize with, as it is easy for them to analyze which phones are regularly in proximity. It is of particular interest to the police to know who is participating in a meeting—if everyone arrives at a meeting with phones, it is easy to determine who was at the meeting, even if all the phones are turned off beforehand.

The only way to defend against location tracking is to avoid habitually carrying your phone around in the first place—to leave your phone at home on a regular basis, not just for sensitive meetings and demonstrations. The more that our communities collectively implement this practice and resist the dominant norm (for example, by making plans in advance rather than relying on constant digital availability), the easier it will be to change our practices on an individual level.

As for data retrieval, if the police gain physical access to a phone, we must assume that they will eventually be able to read its contents. Arrests are often accompanied by a warrant to seize all phones and computers, and many police departments have contracts with companies like Cellebrite that develop technology to bypass disk encryption. A leaked document from July 2024 shows that Cellebrite can unlock almost all Android and iOS phones (with the exception of GrapheneOS, a security-focused variant of Android that we recommend). It’s also important to keep in mind that encrypted messaging apps like Signal do not solve this problem. No mobile phone app is capable of “disappearing” messages from a disk in a way that will ensure that a forensics specialist cannot recover them, because truly erasing data requires reformatting the entire drive. To get an idea of what type of phone data the police are interested in, read the testimony of a J20 defendent whose phone was seized.

It is inconvenient to be careful with our phones, but it is even more inconvenient to end up behind bars. The extensive possibilities for phone surveillance become less threatening when we treat our phones as untrustworthy and leave them at home whenever possible. As stated in a recent security proposal, “Carrying your phone with you has security implications for everyone you interact with.”

Whenever you type something into a phone, consider the possibility that it could eventually be read aloud in court. All truly sensitive conversations should take place in person, outdoors, with phones left at home. Phones are useful for exchanging non-sensitive information or scheduling a meeting time, but not for communicating anything that could be interpreted as evidence of criminal conspiracy. If a plan requires remote communication, consider anonymously purchased “burner phones” or walkie-talkies.

Whenever we are compelled to use digital technology for anything sensitive, we exclusively use the Tails operating system, a Linux variant which runs from a USB stick and leaves no trace on the computer. Take note that the only trustworthy disk-encryption for computers requires using a Linux operating system—it’s not possible to rule out backdoors in Windows and macOS because their source code is not publicly available, and security researchers have repeatedly broken Windows disk encryption.

In The Streets

Demonstrators in Berkeley, California on February 1, 2017.

Becoming Anonymous

When a black bloc forms, participants usually change into their matching black clothing near the meeting point of the demonstration. Individuals filter into the area in civilian clothing, change into black bloc attire to join the black bloc, then change back into civilian clothes to leave the area afterwards. In order to ensure that no one can make a connection between your “civilian” and “bloc” clothing, it is important that these two outfit changes are not documented or witnessed by police, journalists, or anyone else you wouldn’t trust with your freedom. For the same reason, once you start to change clothes, you should do so immediately and completely, with no intermediate stage mixing together elements of both outfits. You can be seen in either civilian or black bloc clothing, but not in a mixture of the two. Even in your civilian outfit, it’s better if it is still difficult to identify you; again, a generic N95 mask and hat can go a long way without attracting too much attention.

Rather than assembling at a convergence point, black blocs can also form on the move, which can make it more difficult for the police to get footage of people changing. This can be easier within a larger crowd.

We change into our bloc clothes in the best place we can find that is out of the sight of cops, surveillance cameras, and filming smartphones. The ideal spot is outside the immediate area that the police are focused on but close enough to the convergence point that you can reach it without being stopped. If there is no better option, we withdraw as deep into the center of the crowd as possible and change while huddled behind banners and umbrellas. Whenever possible, it is better to change beneath awnings, overpasses, or other forms of cover that block the view of drones. In some cases, there will be police specifically tasked with identifying people, and investigators may spend hours afterwards going through all the available footage. It is a good idea to practice changing into and out of the bloc layer ahead of time to make the process quicker and less stressful.

If our outfits serve their purpose, police will have a more difficult time distinguishing between individuals, keeping track of who is who, and providing convincing testimony in court. After changing, we quickly check each other to make sure that no hair, eyebrows, or (ideally) skin remain unconcealed, no clothes from the “civilian layer” are visible, and no other details such as scars, piercings, or tattoos are exposed. To carry materials, we generally favor plain black tote bags over backpacks, as the latter are easier to distinguish. Some backpacks can compress well when worn under a hoodie; this can be helpful for carrying gear we don’t need immediately, such as clothing. If we are going to use protective gear (body armor, helmets, gas masks and goggles), it may be a good idea for participants in the black bloc to decide collectively on a specific model in advance—this way, even if the protective gear has some distinguishing features, at least it won’t be possible to distinguish a black bloc participant on that basis alone.

Sometimes, instead of wearing black bloc clothes, a group makes the decision that it is more appropriate to participate in a demonstration as a light bloc. In this case, rather than dressing head-to-toe in black, participants conceal their faces while wearing everyday clothing such as nondescript hoodies or rain gear, choosing dull colors such as gray and brown. The idea is to blend in with other demonstrators, since police can more easily identify and target a clearly distinguishable bloc.

However, if arrests do occur, it can be easier to convict a “light bloc” demonstrator than a demonstrator participating in a black bloc. Wearing “nondescript” clothing does not render the participants indistinguishable, so it will be easier for an undercover cop, informant, or spectator within the demonstration to reliably track someone they witnessed taking a given action, and easier for a prosecutor to establish a convincing continuity between the person who was seen committing an action and the person who was later arrested. Wearing black clothing with no logos that looks virtually identical to what many others are wearing makes it much harder to establish such continuity, whether through testimony or surveillance footage. Black clothing is hard to distinguish from other black clothing, in contrast to colored clothing, which has distinct shades. The color black also absorbs the most light, making it less likely for body characteristics and details like pockets and hemlines to be identifiable in video footage.

For these reasons, we generally prefer to wear all black whenever there are enough people participating to make it effective. The logic of wearing all black is fairly self-evident, so the tactic has the potential to spread widely in the streets. For instance, during the protests in Philadelphia after the dismissal of charges against the cop who murdered Eddie Irizarry, one report noted that masked looters and rioters were overwhelmingly wearing black clothes.

Making Decisions in the Heat of the Moment

Group decision-making can be difficult when time is short in stressful circumstances. During planning meetings, we aim to discuss proposals extensively and make sure that all the participants have a chance to explain their positions—but that’s not always possible during a demonstration. Consequently, we make sure that everyone is matched with a buddy or two that they stick with throughout the demonstration, so that they can make time-sensitive decisions in smaller, more agile groups.

It’s usually impossible to know whether there are undercovers within earshot, so we’re careful not to use anyone’s real name during demonstrations. We choose a temporary (one-time only!) group name to call out when we need to regroup during a chaotic moment or to signal that we all need to touch base. We also create temporary aliases to identify ourselves if it seems necessary, although simply pointing can usually do the trick.

It’s important to avoid panic or spreading rumors. We try not to make decisions based on unverified information, but rather on what we can observe directly—for example, paying attention to how police are moving in terms of gear, numbers, and vehicles rather than assuming the worst when things get scary. When sharing information, pass on what you have witnessed (“I saw the front line of police putting on gas masks!”) rather than the inference you are drawing from it (“They’re going to gas us!”), so the people you are addressing can draw their own informed conclusions.

When reporting what you have seen yourself, you can use the SALUTE (Size/strength, Activity, Location and direction, Uniform/description, Time and date of observation, Equipment) or ALERTA (Activity, Location, Equipment, Response requested, Time and date, Appearance) protocols to maximize the usefulness of the information you convey.

Demonstrations can become very fast-paced, which can make it challenging to communicate with each other in a thoughtful way, sometimes resulting in hurtful or frustrating interactions. This can be quite difficult to navigate in the moment, especially since everyone reacts to stressful situations differently. We usually find it’s best to address these kinds of dynamics later on, during a debrief.

There are tools for reducing the negative impact of this stress on our physical and mental health and relationships. Every affinity group can benefit from learning about somatic practices for regulating the nervous system under stress and incorporating these into their street action routine.

Police Surveillance

It is always possible that undercover cops will try to infiltrate combative crowds, especially in larger black blocs in which no one participant will recognize all of the others.1 If they take this risk, their goal will probably be to watch who is engaging in high-risk actions, note what those people are wearing after they change clothes, and follow them after the bloc disperses in order to arrest them with the assistance of other police in the area. Several years ago, in one North American city, demonstrators verbally confronted undercover police, who pulled out extendable batons. At subsequent demonstrations in that city, the undercovers either showed up in such a large group that they were impossible to miss, or—apparently—didn’t show up at all. The police are unionized, and even their high salaries aren’t enough to persuade them to risk injury when they can avoid it, especially given that undercovers can’t carry recognizable police protective gear.

The uniformed cops policing the demonstration will often be filming in some capacity, and the quality of this footage can be quite good. Police departments are already using drones to carry out surveillance of demonstrations. Police typically analyze at least some of this footage in real time, while the action is still happening, to facilitate targeted arrests during police charges or in the moments following the dispersal of the demonstration when there is no longer a collective capacity to fight back.

If we ever see police pointing at someone, especially commanding officers, we make sure to let that person know. Sometimes, this may be just for intimidation purposes. If this happens to you, changing clothes when they are focused on you may not solve your problems if the police are able to maintain a line of sight. The last thing you want to do is burn your exit outfit when you are already a target. Make sure to get safely out of their view before you change clothes.

Other Forms of Surveillance

Not only the police will be filming—surveillance cameras, spectators, and even other demonstrators may also be shooting footage. Many participants in the George Floyd uprising were arrested and convicted solely on the basis of this type of evidence. Filming those engaged in high-risk activity is functionally equivalent to testifying against them in court, regardless of your intentions. We try to foster a demonstration culture where there is zero tolerance for filming (whether livestreamers, journalists, or other demonstrators with smartphones), inspired by how black blocs in Portland have sought to normalize this collective expectation after several court cases hinged on this sort of evidence.

The sooner that cameras are removed from the demonstration, the better—ideally, before anything happens that they could document. It’s important to give people who are filming an opportunity to put their devices away when asked. Participants or supporters can distribute flyers during a demonstration that explain why filming is not tolerated. While some livestreamers will stubbornly try to continue putting others’ freedom at risk in hopes of building a social media following, most people simply haven’t given much thought to how filming ultimately helps the police. In any case, when someone continues filming after being told not to, it is perfectly reasonable to assert a boundary. Rather than getting into a distracting scuffle, one option is simply to cover their lenses with spray paint, using a fat cap designed for graffiti, which has long reach.

Unfortunately, even legal observers who exclusively film police arrests can still make it riskier to resist arrest or to de-arrest arrestees. There are many ways to contribute to impeding police that don’t require creating documentary evidence that could be used against people. Barricades, reinforced banners, shields, umbrellas, extinguishing tear gas, lasers, fireworks, flagpoles, fire extinguishers, smoke screens, caltrops , and paint can all serve to prevent arrests from happening in the first place.

Even ordinary cloth banners can play a helpful role by blocking photographers. For this reason—not to mention for the sake of making the messages painted on them visible to spectators—participants in a march should not carry banners in the midst of the crowd, but rather should line the front, sides, and back of the march, holding the banners high enough to conceal the bodies of the participants without blocking their view of the streets around them.

Even well-meaning photographers can pose a threat to demonstrators.

Other Threats

Police will probably be the most powerful threat you have to contend with, but they may not be the most dangerous one. Far-right reactionaries can act more unpredictably and with less restraint. In the United States, at least, this can sometimes involve vehicular attacks or firearms. During the George Floyd Rebellion of 2020, in order to protect crowds against automobiles, it became common practice in some cities to flank demonstrations with cars. This model has obvious drawbacks—it can slow marches and inhibit their mobility, as well as exposing the drivers to legal risk.

Regarding the threat of shooting attacks, you should know the location of the closest hospital with a trauma center and have a plan regarding how to reach it; read this guide detailing how to respond to gunshot wounds during demonstrations. You can attend demonstrations in bullet-resistant body armor, but often it is best simply to focus on remaining aware of your surroundings and quick on your toes.

For now, the likelihood of being endangered by a driver or shot at during a demonstration is not much greater than the likelihood of being endangered by a driver or shot at in any other situation in the United States. The question of how to deal with firearms at demonstrations raises a host of other questions which are beyond the scope of this text.

Beneath the Paving Stones, the Beach

Against a well-resourced adversary trained for symmetrical conflict, the chief strength of demonstrations lies in mobility. Riot police have to carry a lot of heavy gear; this makes it difficult for them to keep up a jog for very long. Their strategy tends to rely on short sprints to disperse or “herd” a crowd before they have to pause or get into a vehicle, and police vans need the streets clear of barricades in order to keep up with a demonstration.

Keeping this in mind, if the numbers are on our side when the cops charge, it is often not necessary to run, and in any case it is important not to panic. A demonstration that moves too fast tends to become less compact, and this can make it easier for the police to single out demonstrators for targeted arrests or to split the demonstration.

At the same time, there are also moments when it may be crucial for a small number of people to act quickly. For example, when a small number of police attempt to form a line to kettle demonstrators, if enough demonstrators can get on the other side of the line, the officers may choose to withdraw rather than risk being surrounded. In Germany, the slogan “five fingers make a fist” has described a variety of tactics involving small groups penetrating police lines in order to come together in a large group on the other side.

Historically speaking, projectiles, fireworks, and barricades can obstruct police from advancing. If you attend a large number of demonstrations, you may end up in a situation in which people are using some of these tactics. Regardless of whether you ever choose to participate in them yourself, it is important that you understand what those people are doing and why.

If people begin employing projectiles, it is crucial to emphasize to everyone that they should only throw things from the front of a crowd. When people throw projectiles over the heads of other demonstrators, this can result in serious injuries. The same goes for throwing projectiles at a target that has people in front of it or beside it. However good the aim, objects sometimes bounce off windows and hit those nearby, or send pieces of broken glass flying. Riot police are equipped with expensive taxpayer-funded protective gear, but demonstrators or passersby could be severely injured.

We have seen groups collect projectiles beforehand in order to empty bags full of them onto the ground between the crowd and the police at the opening of a confrontation, enabling those who arrived empty-handed to join in.

Stones and hammers can both break windows, but each entails different security considerations. Stones can serve a wider array of functions; when no longer needed, if left in an appropriate setting, they will attract less attention from a forensic team than a hammer would. Hammers can be safer to use in a chaotic or crowded situation. They can be used over and over, they are easier to aim, and they are helpful for windows, which are more liable to break when struck in the corners, where the glass is more rigid. If someone breaks a window with a hammer, this will spray tiny particles of glass onto the clothes of anyone nearby, and police have special flashlights to detect these traces, whereas stones can be thrown from a sufficient distance to avoid this issue. Another risk associated with using hammers to break glass is cutting oneself—for example, if the momentum causes the user’s hand to go through the window when it breaks. With a properly weighted construction hammer, a flick of the wrist alone can suffice to generate enough force to break most windows, while holding the arm still and away from shards of glass.

Increasingly, banks, corporate chains, and government buildings are outfitted with expensive windows that are difficult to break. The glass may be thicker and laminated with special layers, or it may feel especially bouncy, typical of polycarbonate panels. We don’t know of a simple method for identifying these stronger window types, and we recommend against spreading myths to the effect that some broad category of windows is “unbreakable.” Often, more force is simply needed, or multiple strikes to the same corner. Chunks of an exceptionally dense material such as porcelain may be more effective than stones.

The Molotov cocktail has been glorified as a symbol of resistance for several decades. But romanticization can be dangerous, obscuring safer and more efficient means of achieving the same goals. Unlike a bottle of accelerant in its original packaging, a Molotov cocktail is legally classified as an “improvised explosive device,” and this intensifies the sentencing guidelines for possessing or using one. Anyone who is considering making or using one should reflect long and hard on the risks involved, including the possibility of serving significant prison time.

The bottom line is that, just as nothing is more dangerous than the imposition of authoritarian “law and order,” there is nothing safer than a city that has spiraled out of control. When the police give up trying to dominate the entire terrain and limit themselves to defending fixed territory,2 many things become possible that are otherwise impossible.

Disappearing Without a Trace

To Fight Another Day

It is important to recognize when the cops have succeeded in regaining control of the situation. Once most of the crowd has dispersed, it is probably time to withdraw. Whether to go home at this point depends on how likely it is that things will pick up again, or if there is still activity somewhere nearby. However, it is best to avoid “grazing”—when groups of people who have just changed out of their bloc clothing mill about in one place, waiting to see if something exciting will happen, without taking any initiative themselves. This provides the police more opportunities to make arrests, while generally not achieving anything useful.

We pay special attention to whether anyone appears to be following us in the minutes after we change out of our bloc layer, so that we can evade them before they have time to coordinate an arrest. We don’t gauge this threat based solely on whether someone looks like a cop—if the police have any sense, they’ll be assigning undercover roles to those who do not look like officers. Rather, we watch to see if any stranger trails us after the demonstration has dispersed. We turn frequently so that anyone in pursuit is forced to make the same illogical series of turns to keep us in sight. If anyone does this, we have to act as though they are an undercover cop or informant. We continue walking calmly until we turn the next corner or otherwise escape their line of sight, then immediately sprint, seeking to break their line of sight repeatedly until we lose them completely. Ideally, we should have escaped by the time they realize that we are evading them. We may keep jogging to exit the area, taking routes that are harder to intercept by bike or car or track via drones—for example, up or down flights of stairs, or through parks, malls, transit stations, pedestrian bridges, and tunnels. We can’t emphasize enough how useful it has been to learn the basic techniques of parkour for things like jumping a fence without rolling an ankle.

It’s always a difficult decision whether to dispose of our bloc clothing and materials soon after dispersing or to carry them further away (for example, in a colorful tote bag, shopping bag, or backpack) before disposing of them. We make this decision in the moment, trying to assess the likelihood that our bags could be searched on our way out of the area. Even if the contents of a bag might not be enough to secure a conviction in a trial, catching charges can still mean months or years of stress and inconvenience. We balance this risk against the risk that an evidence collection team could find items in the vicinity of the demonstration and send them to a forensic lab. If you can safely transport clothing and materials out of the area, you should.

When we discard things, we seek to take advantage of locations where the evidence collection team won’t easily find them. We aim to use separate locations for ditching materials (which we’ve done our best to keep clean of forensic traces) and clothing (which will inevitably retain at least some DNA on it) so that they can’t be easily associated even if they are found. If we’re going to ditch materials, we try to find discreet opportunities to do so before the bloc disperses so that anyone arrested after dispersal will only have clothing on them. Even if we ditch materials, we may still decide to carry out clothing.

When carrying things out of the area, a bag search will be less incriminating if the clothing is indistinguishable from that of other participants in the demonstration. Once we are far enough away from the area, we dispose of everything discreetly—for example, in a dumpster or garbage can.

Sometime the following week, we debrief as a group, outdoors and without phones. What worked? What should we avoid in the future? What did we want to do but couldn’t do? What do we still need to figure out? Is there a need for arrestee support? How are people feeling? Should we (securely and anonymously) publish our reflections on the events? What’s next?

The Best Remedy for Paranoia Is Realism and Good Preparation

During the periods of social peace between flare-ups of widespread social revolt, the forces of repression only have to contend with a relatively small number of adversaries. We take all the countermeasures discussed here because we want to be able to continue taking direct action over the long term, even if significant investigative resources are devoted to repressing the networks we participate in.

That said, it’s important to keep in mind that in the United States context, the vast majority of cases against demonstrators in recent years have relied on just a few sources of evidence that are easy to address:

- Not wearing a (good) mask. It’s inevitable that some people will throw down without donning a mask first. Anarchists can anticipate this and bring a few backpacks full of black T-shirts and gloves to distribute. This can be literally life-changing for people.

- Wearing distinguishable clothing. Thanks to photographs, video footage, and police testimony, and online shopping records, any distinguishable clothing can help identify a suspect.

- Using a phone in an incriminating way—for example, by sending incriminating text messages, or as a consequence of screenshots, photos, search history, social media use, or the phone’s location history.

- Making purchases in an identifiable way. Purchases are easier to link back to an identity if they are made in the weeks before the demonstration, when store surveillance footage remains more accessible to investigators. The same goes when purchases are not made with cash, and likewise when serial numbers or RFID tags remain on the items.

- Having incriminating materials found in a house search. This is why we dispose of all items that can be tied to specific actions and store sensitive items away from home.

Too often, discussions about “security” result in people needlessly limiting themselves. Instead, we want to approach this subject in a way that equips us to realize our aspirations and develop a stronger continuity of resistance. While standing up for each other will always involve risk, we can strive not to make it any easier for them.

Further Reading

- A Demonstrator’s Guide to Body Armor

- A Demonstrator’s Guide to Gas Masks and Goggles—Everything you need to know to protect your eyes and lungs from gas and projectiles.

- A Demonstrator’s Guide to Helmets

- A Demonstrator’s Guide to Police Batons

- A Demonstrator’s Guide to Reinforced Banners

- A Demonstrator’s Guide to Responding to Gunshot Wounds

- A Demonstrator’s Guide to Riot Munitions

- Fashion Tips for the Brave

- The Femme’s Guide to Riot Fashion

- How to Survive a Felony Trial

- Protocols for Common Injuries from Police Weapons

- Confidence, Courage, Connection, Trust: A Proposal for Security Culture

- Dealing With DNA in Practice

- Stop Hunting Sheep: A Guide to Creating Safer Networks

- Threat Library: Digital Best Practices

- You Can’t Catch What You Can’t See: Against Video Surveillance

-

If we make good fashion decisions, people shouldn’t be able to recognize us easily even if they know us, at least not without hearing our voices. ↩

-

This occurred to some extent in Washington, DC on the afternoon of Donald Trump’s inauguration in 2017, and later that year in Hamburg during the G20 protests, but most spectacularly in 2020 during the first days of the George Floyd Rebellion. ↩