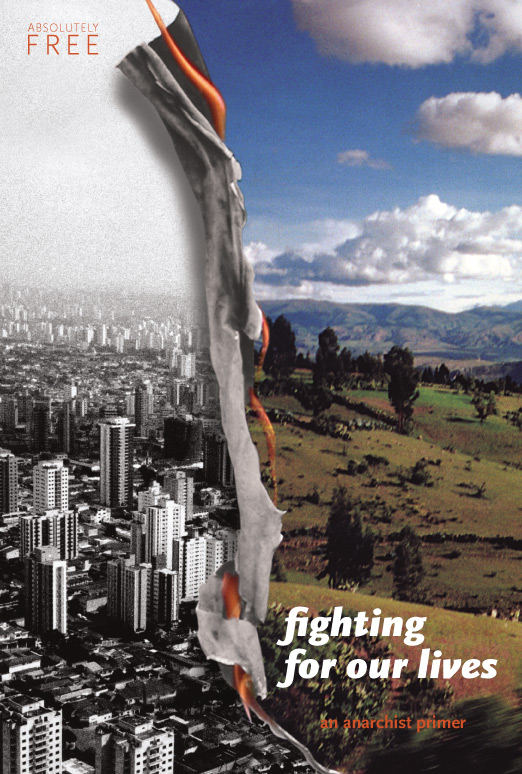

Fifteen years ago, we published a paper introducing anarchism to the general public as a total way of being, at once adventurous and accessible. We offered it free in any quantity, raising tens of thousands of dollars for printing and even offering to cover the postage to mail copies to anyone who could not afford them. In the first two weeks, we sent out 90,000 copies. It appeared just in time for the “People’s Strike” mobilization against the IMF and World Bank in Washington, DC; the pastor at the Presbyterian church that hosted anticapitalist activists in DC preached her Sunday sermon from the primer as she spoke to her congregation about the demonstrations. Over the following decade, Fighting for Our Lives figured in countless escapades and outreach efforts; read this story for an example. In the end, we distributed 650,000 print copies.

Fighting for Our Lives has been out of print for several years, as we’ve focused on other projects such as To Change Everything. From this vantage point, we can appreciate both the text and the project itself as ambitious and exuberant attempts to break with the logic of the existing order and to stake everything on establishing new relations. We’ve learned a lot in the years since then—but we haven’t backed down one millimeter.

Overture: A True Story

We dropped out of school, got divorced, broke with our families and ourselves and everything we’d ever known.

We quit our jobs, violated our leases, threw our furniture out on the sidewalk, and hit the road.

We sat on the swings of children’s playgrounds until our toes were frostbitten, admiring the moonlight on the dewy grass, writing poetry on the wind.

We went to bed early and lay awake past dawn recounting all the awful things we’d done to others and they to us—and laughing, blessing and absolving each other and this crazy cosmos.

We stole into museums showing reruns of old Guy Debord films to write faster, my friend, the old world is behind you on the backs of the theater seats.

The scent of gasoline still fresh on our hands, we watched the new sun rise, and spoke in hushed voices about what we should do next, thrilling in the budding consciousness of our own limitless power.

We used stolen calling card numbers to talk our lovers through phone sex from telephone booths in the lobbies of police stations.

We slipped into the offices where our browbeaten friends shuffled papers for petty despots, to draft anti-imperialist manifestos on their computers and sleep under their desks. They were shocked the morning they finally walked in on us, half-naked, brushing our teeth at the water cooler.

We lived through harrowing, exhilarating moments when we did things we had always thought impossible, spitting in the face of all our apprehensions to kiss unapproachable beauties, drop banners from the tops of national monuments, drop out of colleges… and then gritted our teeth, expecting the world to end—but it didn’t!

We stood or knelt in emptying concert halls, on rooftops under lightning storms, on the dead grass of graveyards, and swore with tears in our eyes never to go back again.

We sat at desks in high school detention rooms, against the worn brick of Greyhound bus stations, on disposable synthetic sheets in the emergency treatment wards of unsympathetic hospitals, on the hard benches of penitentiary dining halls, and swore the same thing through clenched teeth, but with no less tenderness.

We communicated with each other through initials carved into boarding school desks, designs spray-painted through stencils onto alley walls, holes kicked in corporate windows televised on the five o’clock news, letters posted with counterfeit stamps or carried across oceans in friends’ packs, secret instructions coded into emails from anonymous accounts, clandestine meetings in coffee shops, love poetry carved into the planks of prison bunks.

We sheltered illegal immigrants, political refugees, fugitives from justice, and adolescent runaways in our modest homes and beds, as they too sheltered us.

We improvised recipes to bake each other cookies, cakes, breakfasts in bed, weekly free meals in the park, great feasts celebrating our courage and kinship so we might taste their sweetness on our very tongues.

We entrusted each other with our hearts and appetites, together composing symphonies of caresses and pleasure, making love a verb in a language of exaltation.

We wreaked havoc upon their gender norms and ethnic stereotypes and cultural expectations, showing with our bodies and our relationships and our desires just how arbitrary their supposed laws of nature were.

We wrote our own music and performed it for each other, so when we hummed to ourselves we could celebrate our companions’ creativity rather than repeat the radio’s dull drone.

In borrowed attic rooms, we tended ailing foreign lovers and struggled to write the lines that could ignite the fires dormant in the multitudes around us.

In the last moment before dawn, flashlights tight in our shaking hands, we dismantled the power boxes on the buildings where fascists were to host rallies the following day.

We fought those fascists tooth, nail, and knife in the streets, when no one else would even confront them in print.

We planted gardens in abandoned lots, hitchhiked across continents in record time, tossed pies in the faces of kings and bankers.

We played saxophones together in the darkness of echoing caves in West Virginia.

In Paris, armed with cobblestones and parasols, we held the gendarmes at bay for nights on end, until we could almost taste the new world coming through the tear gas.

We fought our way through their lines to the opera house and took it over, and held discussions there twenty-four hours a day as to what that new world should be.

In Chicago, we helped create an underground network to provide illegal abortions in safe conditions and a supportive atmosphere, when the religious fanatics would have preferred us to die in shame and tears down dark alleys.

In New York, we held hands and massaged each other’s shoulders as our enemies closed in to arrest us.

In Quebec, we tore up the highway and pounded out primordial rhythms on the traffic signs with the fragments, and the sound was vaster and more beautiful than any song ever performed in a concert hall.

In Santiago, we robbed banks to fund papers of transgressive poetry.

In Siberia, we plotted impossible escapes—and carried them out, circumnavigating the globe with forged papers and borrowed money to return to the arms of our friends.

In Montevideo, in the squatted township, we built huts from plywood and plastic sheeting, pirated electricity from nearby power lines, and conferred with our neighbors as to how we could contribute to our new community.

In San Diego, when they jailed us for speaking our minds, we invited our friends and filled their prisons until they had to change their policies.

In Oregon, we climbed trees and lived in them for months to protect the forests we had hiked and camped in as children.

In Mexico, when we met hopping freight trains, we traded stories about working with the Zapatistas in Chiapas, about floods witnessed from boxcars passing through Texas, about our grandparents who fought in the Mexican revolution.

We fought in that revolution, and the Spanish civil war, and the French resistance, and even the Russian revolution—though not for the Bolsheviks or the Tsar.

Sleepless and weather-beaten, we crossed the Ukraine on horseback to deliver news of the conflicts that offered us another chance to fight for our freedom.

Tense but untrembling, we smuggled posters, books, firearms, fugitives, ourselves across borders from Canada to Pakistan.

We lied with clean consciences to homicide detectives in Reno and military police in Santos.

We told the truth to each other, even truths no one had ever dared tell before.

When we couldn’t overthrow governments, we raised new generations who would taste the sweet adrenaline of barricades and wheatpaste, who would carry on our quixotic quest when we fell or fled before the ruthless onslaught of the servile and craven.

When we could overthrow governments, we did.

We stood behind the witness stand, one after another, decade after decade, century after century, and shouted so the deafest self-satisfied upright citizen at the back of the courtroom could hear it: “… and if I could do it all over again, I would!”

As the sun rose after winter parties in unheated squats, we gathered up great sacks of broken glass and washed stacks of dirty dishes in freezing water, while our critics, sequestered in penthouses with maid service, demanded to know who would take out the garbage in our so-called utopia.

When the good intentions of liberals and reformists broke down in bureaucracy, we collected food from the trash to feed the hungry, broke into condemned buildings and transformed them into palaces fit for pauper kings and bandit queens, held the sick and dying tight in our loving arms.

We fell in love in the wreckage, shouted out songs in the uproar, danced joyfully in the heaviest shackles they could forge; we smuggled our stories through the gauntlets of silence, starvation, and subjugation, to bring them back to life again and again as bombs and beating hearts; we built castles in the sky from the ruins of hell on earth.

One of us even assassinated the President of the United States.

Accepting no constraints from without, we countenanced none within ourselves, either, and found that the world opened before us like the petals of a rose.

I’m speaking, of course, of anarchists—and when people ask me about my politics, I tell them: the best reason to be a revolutionary is that it is simply a better way to live. Their laws guarantee us the right to remain silent, the right to a public trial by a jury of our peers (though my peers wouldn’t put me on trial—would yours?)—what about the right to live life like we won’t get another chance, to have reasons to stay up all night in urgent conversation, to look back on every day without regret or bitterness? Such rights we can only claim for ourselves—and shouldn’t these be our central concerns, not the minutiae of protocol and survival?

For those of us born into a captivity gilded by the blood and sweat of less fortunate captives, the challenge of leading a life worth living of stories worth telling is a lifelong project, and a formidable one; but all it takes, at any moment, to meet this challenge is to contest that captivity.

When we fight, we’re fighting for our lives.

You can read this text online here.